- Published on

Using Git

- Authors

- Name

- Ashish Thanki

- @ashish__thanki

A version control system (VCS) is arguably one of the most important tools a data scientist can have when working within a team. It allows you to easily track changes to files, resolve issues quickly, and develop code to enable multiple developers to work together in a small or large project. Git is the most popular VCS because it is free and open source, and also extremely easy to use (with a bit of a learning curve). Git can be downloaded here - in case you were wondering the 'scm' on the website URL stands for its 'source code management'.

This blog highlights the key commands that would be required when using git. Note, please refer to the further reading material if you are not familiar with git and then come back here when you need a reference guide!

Git Commands

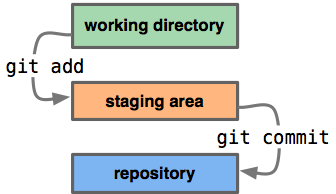

git add <files-to-add> or replace with a regex pattern, such as . for all files currently not staged.

git commit commits all files currently staged.

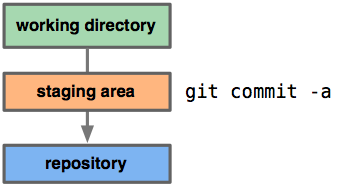

git commit -a -m 'insert commit message' adds and commits all files changed and not tracked.

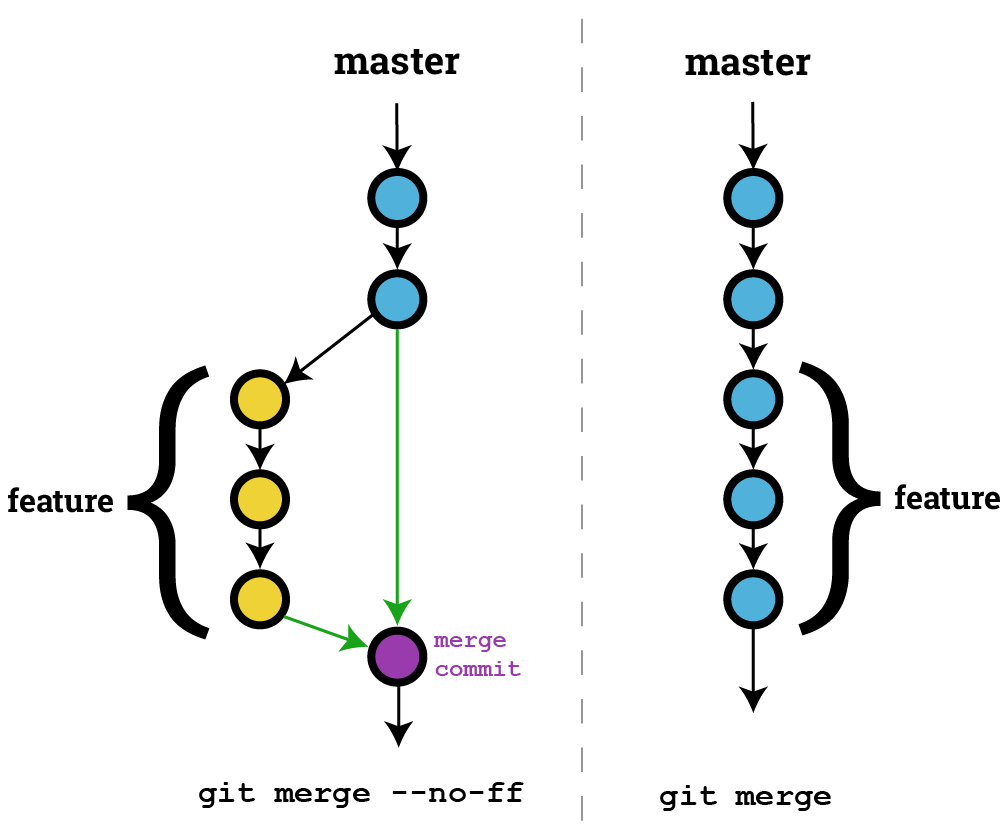

git merge merges branches together. The default behavior is a fast forward merge, where it carries out the merge only if there is a direct linear path from the source branch to the target branch. If successful, git does not create a merge commit. Meanwhile, a three-way merge is used when there is a larger group of features being introduced, or when there are multiple developers working within the project simultaneously. This type of method creates a merge commit, where it attempts to tie the branches histories together.

git branch -l lists all branches.

git branch -D <branch-name> deletes the branch name.

git checkout <branch-name> switches branches or restores current working tree.

git checkout -b <branch-name> creates a new branch and switches to that branch.

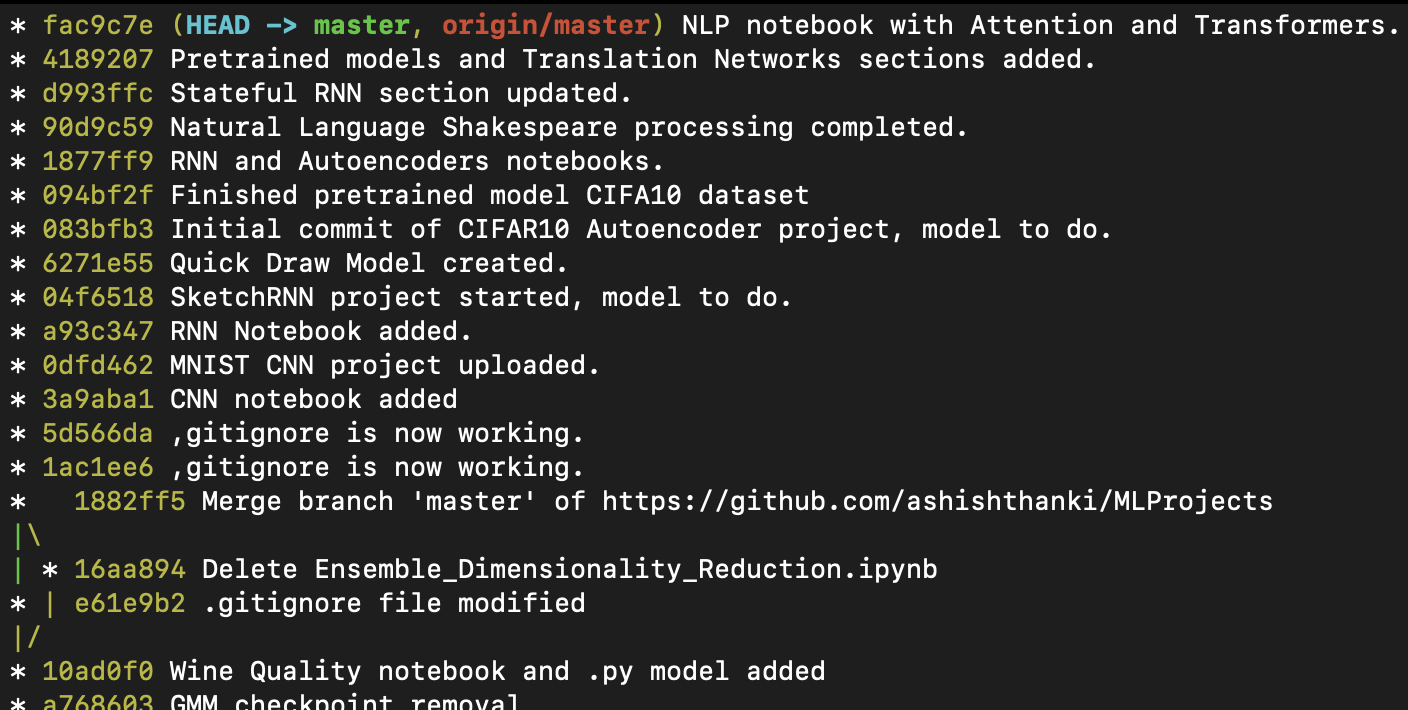

git log shows the most recent commits along with the descriptions.

git log --graph --oneline provides a summarized view of the commits within the current repository in a graph like format.

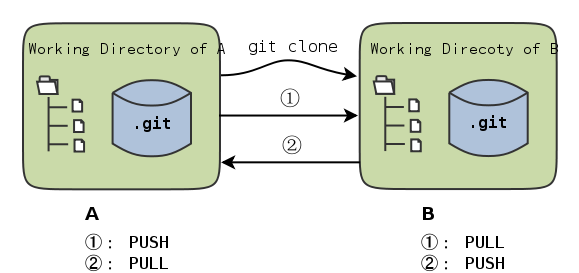

git clone <url> clones the repository provided within the URL.

git pull fetches and downloads content from the remote repository to update the local repository so that it matches that content.

git push uploads the local repository to the remote.

git stash can be used when you want to save your local modifications but you want to work on another branch and not ready to commit your current changes. After calling the stash command you get back a message as WIP on <branch-name>.... Once you have finished working on the branch, through a commit, you can get back the stashed modifications by calling git stash pop.

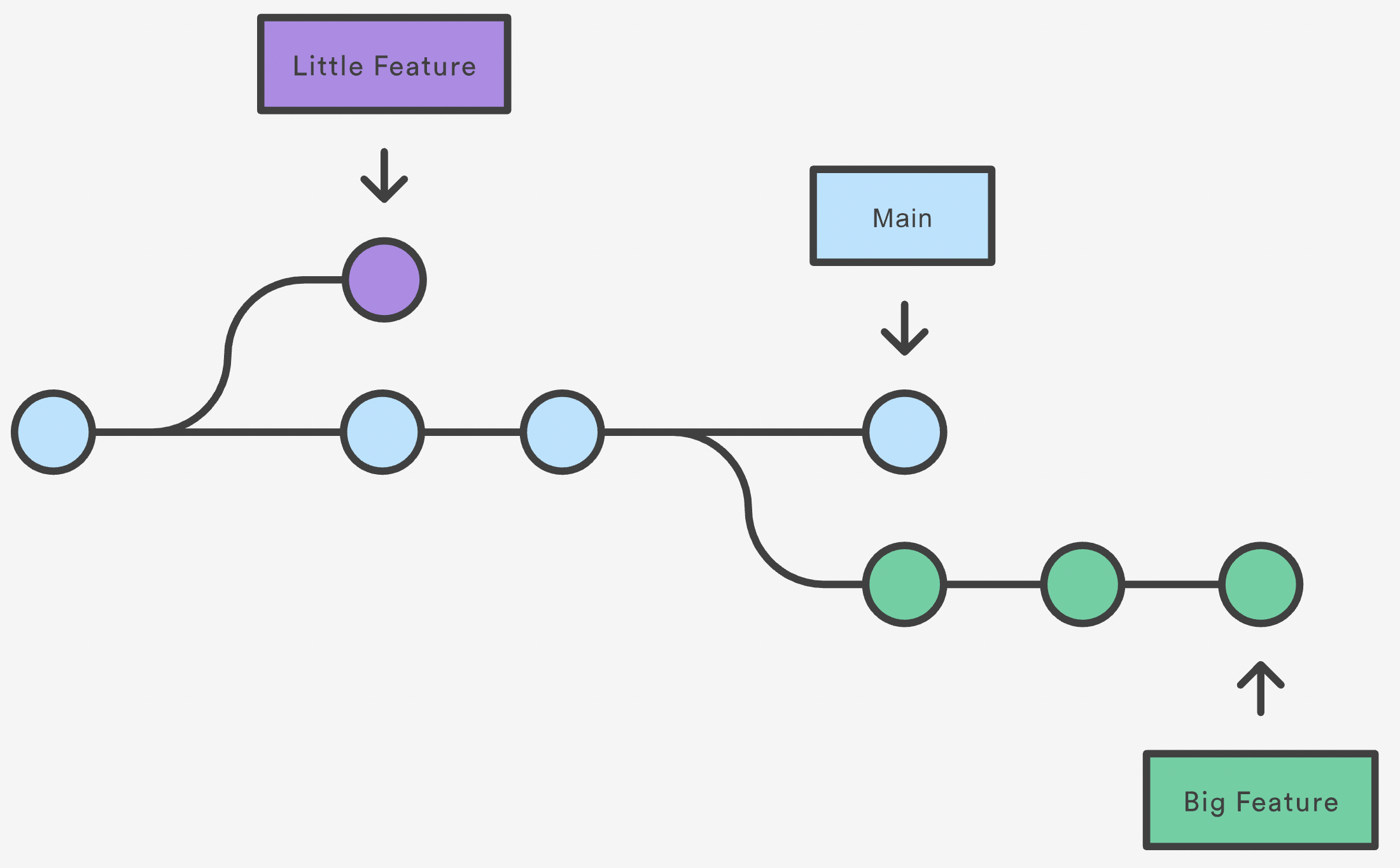

When working as a team or collaborating on GitHub, you can use pull requests so that the modifications you have made can be merged into the project. You may often want to combine multiple commits into one commit to avoid cluttering the commit history and keeping it linear. This is where git rebase -i alongside squash can be used, read more here.

To rebase you take all the changes that you made on one branch and replay them onto another branch. For example, we first checkout the new feature git checkout <new-feature> then call git rebase master. This goes to the common ancestor of the two branches and resets the current branch to the same commit you are rebasing onto, effectively, applying each commit that was made on the master branch to the <new-feature> branch (since the common ancestor). Once finished we can then go back to the master branch and merge the <new-feature> branch onto. This is how the workflow goes:

$ git checkout new-feature

$ git rebase master

...

$ git checkout master

$ git merge new-feature # note, this is a fast forward merge but there could be conflicts.

Yes, git rebase is similar to git merge but keeps the commits history linear. You should never use rebase on remote repositories. You should only use rebase locally, or if you really understand what implications rebase will have on the remote repository.

Another way to keep your commits linear is by using --squash flag on the git merge command. This squashes a series of commits into a single commit.

Rewriting history is not allows the best thing to do and should be avoided. However, there will be times when you may want to squash all your commits into a single commit. Similar to how rebase effectively changes the history, git squash does not touch the source branch and creates a single commit within that branch. Meanwhile, rebase goes onto the same source branch. Read more about the comparison at this StackOverflow post.

That is it! Those are the git commands that you will use, there are plenty more commands that I have not discussed here, that expand on the versatility that git offers. Check them out here.

Best Practices

Other than the git commands, it is useful to understand the best practices of using git within a team:

- It is common practice to keep the latest version in the master branch and the latest stable version in a separate branch.

- Avoid large commits with many changes. Split your commits into smaller chunks.

- Always synchronize your branches before starting any work on your own. This allows you to start from the most recent version, minimizing chances of conflicts or the need for rebasing.

- Never rebase on the remote branch, unless you know the implications this will have on your project.

- Clear commit messages. More documentation the better!

Conclusion

I hope this blog has helped but there are many videos, e-learning courses and blogs out there explaining Git that can expand on the commands I have discussed. I hope you can now answer the questions:

- Why do I need Git?

- How do I get started?

- What commands do I need?

- When will I use Git?

Nowadays Git can be used alongside many extensions that make your git workflow a lot easier, but understanding how it works beneath the extension is crucial in helping you resolve more complex issues as they arise. Git is a crucial tool when performing code reviews, check out Google's code style guide and this well written story on code review workflows.